22 Jan The modern diet dilemma: Is it better to… eat meat? Go vegan? Something in between? The truth about what’s right for you.

Some vegans believe meat causes cancer and destroys the planet. But meat-eaters often argue that giving up animal foods leads to nutritional deficiencies. Both sides say their approach is healthier. What does science say? And how can you best help clients, no matter their dietary preferences? Keep reading for the answers.

++++

Put a group of vegans and Paleo enthusiasts in the same social media thread, and one thing is nearly 99 percent certain: They’ll start arguing about food.

“Meat causes cancer!”

“You need meat for B12!”

“But meat production leads to climate change!”

“Meat-free processed food is just as bad!”

And on it will go.

Let’s just say that, when it comes to the vegan vs. meat-eater debate, people have thoughts, and they feel strongly about them.

Who’s right?

And which approach is right for you?

And what should you tell your clients?

As it turns out, the answers to those questions are nuanced.

In this article, you’ll find our take on the vegetarian vs. meat-eater debate, which you may find surprising—potentially even shocking—depending on your personal beliefs.

You’ll learn:

- The real reasons plant-based diets may lower risk for disease.

- Whether eating red and processed meat raises risk for certain diseases.

- How to eat for a better planet.

- Why some vegetarians feel better when they start eating meat—and, conversely, why some meat-eaters feel better when they go vegetarian.

- How to help your clients (or yourself) weigh the true pros and cons of each eating approach.

Vegan vs. vegetarian vs. plant-based vs. omnivore: What does it all mean?

Different people use plant-based, vegetarian, vegan, and other terms in different ways. For the purposes of this article, here are the definitions we use at Precision Nutrition.

Plant-based diet: Some define this as “plants only.” But our definition is broader. For us, plant-based diets consist mostly of plants: vegetables, fruits, beans/legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. In other words, if you consume mostly plants with some animal-based protein, Precision Nutrition would still consider you a plant-based eater.

Whole-food plant-based diet: A type of plant-based diet that emphasizes whole, minimally processed foods.

Fully plant-based / plant-only diet: These eating patterns include only foods from the plant/fungi kingdom without any animal products. Fully plant-based eaters don’t consume meat or meat products, dairy, or eggs. Some consume no animal byproducts at all—including honey.

Vegan diet: A type of strict, fully plant-based diet that tends to include broader lifestyle choices such as not wearing fur or leather. Vegans often attempt to avoid actions that bring harm or suffering to animals.

Vegetarian diet: “Vegetarian” is an umbrella term that includes plant-only diets (fully plant-based / plant-only / vegan) as well as several other plant-based eating patterns:

- Lacto-ovo vegetarians consume dairy and eggs.

- Pesco-pollo vegetarians eat fish, shellfish, and chicken.

- Pescatarians eat fish and shellfish.

- Flexitarians eat mostly plant foods as well as occasional, small servings of meat. A self-described flexitarian seeks to decrease meat consumption without eliminating it entirely.

Omnivore: Someone who consumes a mix of animals and plants.

Now that we know what the terms mean, let’s turn to the controversy at hand.

The Health Benefits of Vegetarian vs. Omnivore Diets

Many people assume that one of the big benefits of plant-only diets is this: They reduce risk for disease.

And a number of studies support this.

For example, when researchers in Belgium asked nearly 1500 vegans, vegetarians, semi-vegetarians, pescatarians, and omnivores about their food intake, they found that fully plant-based eaters scored highest on the Healthy Eating Index, which is a measure of dietary quality.

Omnivores (people who eat at least some meat) scored lowest on the Healthy Eating Index and the other groups scored somewhere in between. Meat eaters were also more likely than other groups to be overweight or obese.1

Other research has also linked vegetarian diets with better health indicators, ranging from blood pressure to waist circumference.2

So, is the case closed? Should we all stop eating steaks, drinking lattes, and making omelets?

Not necessarily.

That’s because your overall dietary pattern matters a lot more than any one food does.

Eat a diet rich in the following foods and food groups and it likely doesn’t matter all that much whether you include or exclude animal products:

- minimally-processed whole foods

- fruits and vegetables

- protein-rich foods (from plants or animals)

- whole grains, beans and legumes, and/or starchy tubers (for people who eat starchy carbs)

- nuts, seeds, avocados, extra virgin olive oil, and other healthy fats (for people who eat added fats)

Of the foods we just mentioned, most people—and we’re talking more than 90 percent—do not consume enough of one category in particular: fruits and vegetables. Fewer than 10 percent of people, according to the Centers for Disease Control, eat 1.5 to 2 cups of fruit and 2 to 3 cups of vegetables a day.3

In addition, other research has found that ultra-processed foods (think chips, ice cream, soda pop, etc.) now make up nearly 60% of all calories consumed in the US.4

Fully plant-based eaters score higher on the Healthy Eating Index not because they forgo meat, but rather because they eat more minimally-processed whole plant foods such as vegetables, fruits, beans, nuts, and seeds.

Since it takes work—label reading, food prep, menu scrutiny—to follow this eating style, they may also be more conscious of their food intake, which leads to healthier choices. (Plant-based eaters also tend to sleep more and watch less TV, which can also boost health.)

And meat-eaters score lower not because they eat meat, but because of a low intake of whole foods such as fish and seafood, fruit, beans, nuts, and seeds. They also have a higher intake of refined grains and sodium—two words that usually describe highly-processed foods.

Meat-eaters, other research shows, also tend to drink and smoke more than plant-based eaters.5

In other words, meat may not be the problem. A diet loaded with highly-processed “foods” and virtually devoid of whole, plant foods, on the other hand, is a problem, regardless of whether the person following that diet eats no meat, a little meat, or a lot of meat.6

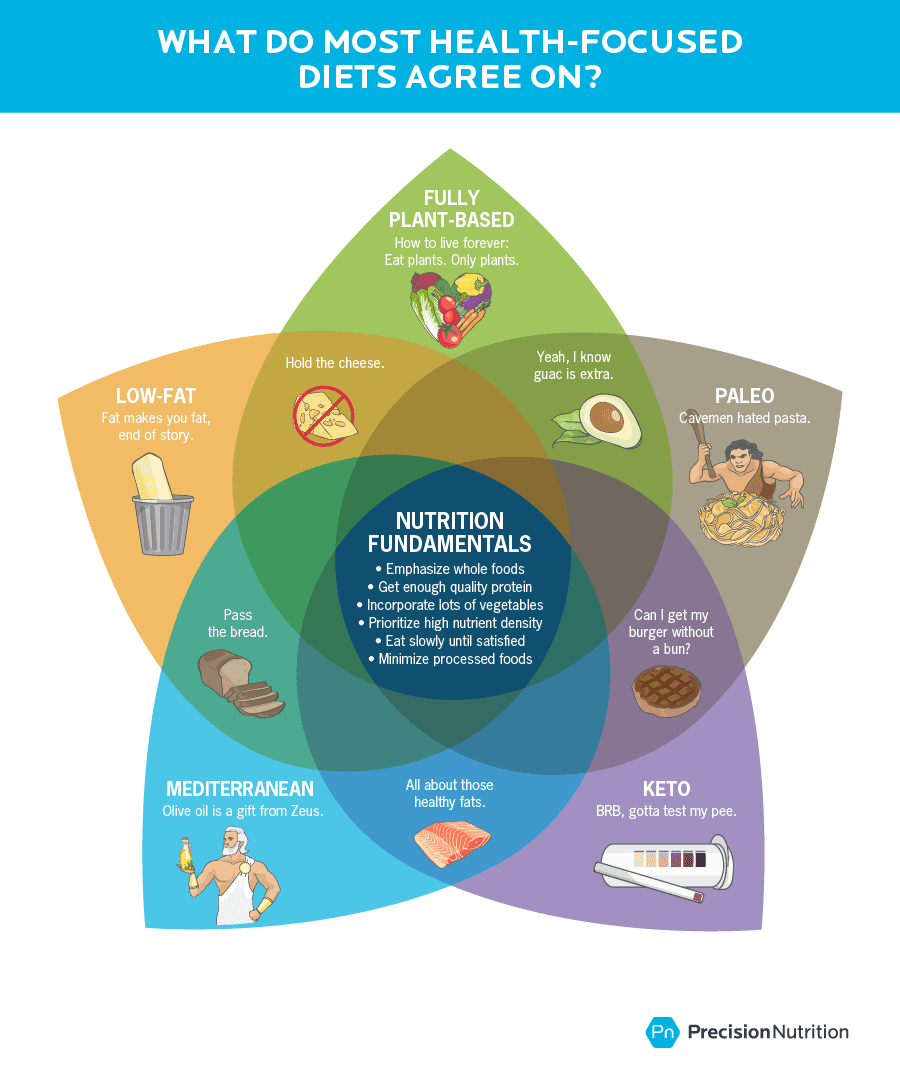

Now check out the middle of the Venn diagram below. It highlights the foundational elements of a healthful diet that virtually everyone agrees on, no matter what their preferred eating style.

These are the nutritional choices that have the greatest positive impact on your health.

Does meat cause cancer?

For years, we’ve heard that meat-eating raises risk for cancer, especially when it comes to red and processed meat.

And research suggests that red and processed meat can be problematic for some people.

Processed meat—lunch meat, canned meat, and jerky—as well as heavily grilled, charred, or blackened red meat can introduce a host of potentially carcinogenic compounds to our bodies.7,8 (This article offers a deeper dive into these compounds.)

Several years ago, after reviewing more than 800 studies, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a part of the World Health Organization, determined that each daily 50-gram portion of processed meat—roughly the amount of one hotdog or six slices of bacon—increased risk of colon cancer by 18 percent.

They listed red meat as “probably carcinogenic” and processed red meat as “carcinogenic,” putting it in the same category as smoking and alcohol.9

So no more bacon, baloney, salami, or hotdogs, right?

Again, maybe not.

First, we want to be clear: We don’t consider processed meat a health food. In our Precision Nutrition food spectrum, we put it in the “eat less” category.

But “eat less” is not the same as “eat never.”

Why? Several reasons.

First, the research is a bit murky.

Several months ago, the Nutritional Recommendations international consortium, made up of 14 researchers in seven countries, published five research reviews based on 61 population studies of more than 4 million participants, along with several randomized trials, to discern the link between red meat consumption and disease.

Cutting back on red meat offered a slim benefit, found the researchers, resulting in 7 fewer deaths per 1000 people for red meat and 8 fewer deaths per 1000 people for processed meat.10

(The study’s main author, though, has been heavily criticized for having ties to the meat industry. Some people have also questioned his methods. This article provides an in-depth analysis.)

Overall, the panel suggested that adults continue their current red meat intake (both processed and unprocessed), since they considered the evidence against both types of meat to be weak, with a low level of certainty.

In their view, for the majority of individuals, the potential health benefits of cutting back on meat probably do not outweigh the tradeoffs, such as:

- impact on quality of life

- the burden of modifying cultural and personal meal preparation and eating habits

- challenging personal values and preferences

Second, the IARC does list processed meat in the same category as cigarettes—because both do contain known carcinogens—but the degree that they increase risk isn’t even close.

To fully explain this point, we want to offer a quick refresher on two statistical terms—“relative risk” and “absolute risk”—that many people tend to confuse.

Relative risk vs. absolute risk: What’s the difference?

In the media, you often hear that eating X or doing Y increases your risk for cancer by 20, 30, even 50 percent or more. Which sounds terrifying, of course.

But the truth? It depends on what kind of risk they’re talking about: relative risk or absolute risk. (Hint: It’s usually relative risk.)

Let’s look at what each term means and how they relate to each other.

Relative risk: The likelihood something (such as cancer) will happen when a new variable (such as red meat) is added to a group, compared to a group of people who don’t add that variable.

On average, studies have found that every 50 grams of processed red meat eaten daily—roughly equivalent to one hot dog or six slices of bacon—raises relative risk for colon cancer by about 18 percent.11

Like we said, that certainly sounds scary.

But keep reading because it’s not as dire as it seems.

Absolute risk: The amount that something (such as red meat) will raise your total risk of developing a problem (such as cancer) over time.

Your absolute risk for developing colon cancer is about 5 percent over your lifetime. If you consume 50 grams of processed red meat daily, your absolute risk goes up to 6 percent. This is a 1 percent rise in absolute risk. (Going from 5 percent to 6 percent is, you guessed it, an 18 percent relative increase.)

So, back to smoking. Smoking doubles your risk of dying in the next 10 years. Smoking, by the way, also accounts for 30 percent of all cancer deaths, killing more Americans than alcohol, car accidents, suicide, AIDS, homicide, and illegal drugs combined.

That’s a lot more extreme than the 1 percent increase in lifetime risk you’d have by eating a daily hot dog.

Finally, how much red and processed meat raises your risk for disease depends on other lifestyle habits—such as exercise, sleep, and stress—as well as other foods you consume.

Getting plenty of sleep, exercising regularly, not smoking, and eating a diet rich in vegetables, fruits and other whole foods can mitigate your risk.

Is processed meat the best option around? No.

Must you completely part ways with bacon, ham, and franks? No.

If you have no ethical issues with eating animals, there’s no need to ban red and processed meat from your dinner plate. Just avoid displacing other healthy foods with meat. And keep intake moderate.

Think of it as a continuum.

Rather than eating less meat, you might start by eating more fruits and vegetables.

You might go on to swap in whole, minimally-processed foods for ultra-processed ones.

Then you might change the way you cook meat, especially the way you grill.

And then, if you want to keep going, you might look at reducing your intake of processed and red meat.

Okay, but at least plants are better for the planet. Right?

The answer, yet again, is pretty nuanced.

Generally speaking, consuming protein from animals is less efficient than getting it straight from plants. On average, only about 10 percent of what farm animals eat comes back in the form of meat, milk, or eggs.

Unlike plants, animals also produce waste and methane gasses that contribute to climate change. “Raising animals for slaughter requires a lot of resources and creates a lot of waste,” explains Ryan Andrews, MS, MA, RD, CSCS, author of A Guide to Plant-Based Eating and adjunct professor at SUNY Purchase.

For those reasons, a gram of protein from beef produces roughly 7.5 times more carbon than does a gram of protein from plants. Cattle contribute to about 70 percent of all agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, while all plants combined contribute to just 4 percent.12

But that doesn’t necessarily mean you must completely give up meat in order to save the planet. (Unless, of course, you want to.)

For a 2019 study in the journal Global Environmental Change, researchers from Johns Hopkins and several other universities looked at the environmental impact of nine eating patterns ranging from fully plant-based to omnivore.13

Notably, they found:

- Reducing meat intake to just one meal a day cuts your environmental impact more than does a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet.

- An eating pattern that includes small, low on the food chain creatures—think fish, mollusks, insects, and worms—poses a similar environmental impact as does a 100 percent plant-only diet.

In other words, if reducing your environmental impact is important to you, you don’t necessarily need to go fully plant-based to do it. You could instead try any of the strategies below.

(And if you’re not interested in taking environmental actions right now, that’s totally okay, too. Ultimately, that’s a personal choice.)

5 ways to reduce the environmental impact of your diet

1. Limit your meat intake.

Consider capping your consumption at 1 to 3 ounces of meat or poultry a day and your consumption of all animal products to no more than 10 percent of total calories, suggests Andrews.

For most people, this one strategy will reduce meat intake by more than half. Replacing meat with legumes, tubers (such as potatoes), roots, whole grains, mushrooms, bivalves (such as oysters), and seeds offers the most environmental benefit for your buck.

2. Choose sustainably raised meat, if possible.

Feedlot animals are often fed corn and soy, which are generally grown as heavily-fertilized monocrops. (Monocropping uses the same crop on the same soil, year after year).

These sorts of heavily fertilized crops lead to nitrous oxide emissions, a greenhouse gas, but crop rotation (changing the crops that are planted from season to season) can reduce these greenhouse gasses by 32 to 315 percent.14

Cattle allowed to graze on grasses (which requires a considerable amount of land), on the other hand, offer a more sustainable option, especially if you can purchase the meat locally.

3. Eat more meals at home.

Homemade meals require less packaging than commercially-prepared ones, and they also tend to result in less food waste.

4. Purchase locally-grown foods.

In addition to reducing transportation miles, local crops tend to also be smaller and more diversified. Veggies grown in soil also produce fewer emissions than veggies grown in greenhouses that use artificial lights and heating sources.

5. Slash your food waste.

As food rots in landfills, it emits greenhouse gasses. “Wasted food is a double environmental whammy,” explains Andrews. “When we waste food, we waste all of the resources that went into producing the food. When we send food to the landfill, it generates a lot of greenhouse gases.”

Made from plant proteins (usually wheat, pea, lentils, or soy) and heme (the iron-containing compound that makes meat red), several meat-like foods have popped up recently, including the Impossible Burger and the Beyond Meat Burger.

So should you give up beef burgers and opt to eat only Impossible Burgers (or another plant-based brand) instead?

The answer depends on how much you like beef burgers.

That’s because the Impossible Burger is not healthier than a beef burger. It’s just another option.

It contains roughly the same number of calories and saturated fat as a beef burger. It also has more sodium and less protein.

And, much like breakfast cereal, it’s fortified with some vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

Rather than a health food, think of the Impossible Burger as a meat substitute that doesn’t come from a farm dependent on prophylactic antibiotics, which can lead to antibiotic resistance. If you want to go out and get a burger with friends, this is one way to do it.

But meat-like burgers are not equal to kale, sweet potatoes, quinoa, and other whole foods.

The same is true of pastas, breads, and baked goods that are fortified with pea, lentil, and other plant protein sources.

These options are great for people who lead busy, complex lives—and especially helpful when used as a substitute for less healthy, more highly-refined options. But they’re not a substitute for real, whole foods like broccoli.

Whether the Impossible Burger is right for your clients depends a lot on their values and where they are in their nutritional journey.

If clients want to give up meat for spiritual reasons (for example, they can’t stand the thought of killing an animal), but aren’t ready to embrace a diet rich in tofu, beans, lentils, and greens, protein-enriched meat-free substitutes may be a good way to help them align their eating choices with their values.

Isn’t meat the best source of iron—not to mention a lot of other nutrients?

Meat eaters sometimes argue that one of the cons of a vegetarian diet is this: Without meat, it’s harder to consume enough protein and certain minerals.

And there may be some truth to it.

Meat, poultry, and fish come packed with several nutrients we all need for optimal health and well-being, including protein, B vitamins, iron, zinc, and several other minerals.

When compared to meat, plants often contain much lower amounts of those important nutrients. And in the case of minerals like iron and zinc, animal sources are more readily absorbed than plant sources.

Remember that study out of Belgium that found vegans had a healthier overall dietary pattern than meat-eaters? The same study found that many fully plant-based eaters were deficient in calcium.1

Compared to other groups, fully plant-based eaters also took in the lowest amounts of protein.

Plus, they ran a higher risk of other nutrient deficiencies, such as vitamin B12, vitamin D, iodine, iron, zinc, and omega-3 fats (specifically EPA and DHA).

Is this proof that everyone should eat at least some meat?

Not really. It just means that fully plant-based eaters must work harder to include those nutrients in their diets (or take a supplement in the case of B12).

This is true for any diet of exclusion, by the way. The more foods someone excludes, the harder they have to work to include all of the nutrients they need for good health.

Vegetarian diets make it easier to reduce disease risk as well as carbon emissions, but harder to consume enough protein, along with a host of other nutrients. This is especially true if someone is fully plant-based or vegan. If your client is fully plant-based, work with them to make sure they’re getting these nutrients.

Protein: Seitan, tempeh, tofu, edamame, lentils, and beans. You might also consider adding a plant-based protein powder

Calcium: Dark leafy greens, beans, nuts, seeds, calcium-set tofu, fortified plant milks

Vitamin B12: A B12 supplement

Omega-3 fats: Flax seeds, chia seeds, hemp seeds, walnuts, dark leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, and/or algae supplements

Iodine: Kelp, sea vegetables, asparagus, dark leafy greens, and/or iodized salt

Iron: Beans, lentils, dark leafy greens, seeds, nuts and fortified foods

Vitamin D: Mushrooms exposed to ultraviolet light, fortified plant milks, and sun exposure

Zinc: Tofu, tempeh, beans, lentils, whole grains, nuts, and seeds

To help you consume enough of these nutrients each day, as part of your overall intake, aim for at least:

- 3 palm-sized portions of protein-rich plant foods,

- 1 fist-sized portion of dark leafy greens,

- 1-2 cupped handfuls of beans*

- 1-2 thumb-sized portions of nuts and/or seeds

* Only need 1 portion as a carb source if also using beans as a daily protein source.

But this plant-based influencer started eating meat—and she says she feels great. Doesn’t that prove something?

Maybe you’ve read about Alyce Parker, a formerly fully plant-based video blogger, who tried the carnivore diet (which includes only meat, dairy, fish, and eggs) for one month. She says she ended the month leaner, stronger, and more mentally focused.

Here’s the thing. You don’t have to search the Internet too long to find a story in the reverse.

A while back, for example, John Berardi, PhD, the co-founder of PN, tried a nearly vegan diet for a month to see how it affected his ability to gain muscle.

During his veggie challenge, he gained nearly 5 pounds of lean body mass.

So what’s going on? How could one person reach their goals by switching to a meat-heavy diet and another do so by giving up meat?

One or more of the following may be going on:

Dietary challenges tend to make people more aware of their behavior.

And awareness provides fertile ground for healthy habits.

New eating patterns require shopping for, preparing, and consuming new foods and recipes. This calls for energy and focus, so people invariably pay more attention to what and how much they eat.

An interesting study bears this out. Researchers asked habitual breakfast skippers to eat three meals a day and habitual breakfast eaters to skip breakfast and eat just two.

Other groups continued breakfast as usual—either skipping it (if they didn’t eat it to begin with) or eating it (if they were already breakfast enthusiasts).

After 12 weeks, the study participants who changed their breakfast habits—going from eating it to skipping it or skipping it to eating it—lost 2 to 6 more pounds than people who didn’t change their morning habits.

Whether or not people ate breakfast mattered less than whether they’d recently changed their behavior and become more aware of their intake.15

Dietary changes may fix mild deficiencies.

People who follow restrictive eating patterns, whether they’re fully plant-based or carnivore, run the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

By switching to a different, just as restrictive eating pattern, people may fix one deficiency—but eventually cause another.

Dietary changes may solve subtle intolerances.

Fully plant-based eaters, for example, who have trouble digesting lectins (a type of plant protein that resists digestion) will probably feel better on a meat-only diet.

But they could also potentially solve the problem without any meat—just by soaking and rinsing beans (which helps to remove lectins). Or by eating some meat and fewer lectin-rich foods.

Finally, the placebo effect is powerful.

When we believe in a treatment, our brains can trigger healing—even if the treatment is fake or a sham (such as a sugar pill). For this reason, as long as someone believes in a dietary change, that change has the potential to help them feel more energized and focused.

Bottom line: Any eating pattern can be healthy or unhealthy.

Someone can technically follow a fully-plant based diet without eating any actual whole plants.

For example, all of the following highly refined foods are meat-free: snack chips, fries, sweets, sugary breakfast cereals, toaster pastries, soft drinks, and so on. And meat-eaters might also include similar foods.

Vegetarian and carnivore diets only indicate what people eliminate—and not what people include.

Whether someone is on the carnivore diet, the keto diet, the Mediterranean diet, or a fully plant-based diet, the pillars of good health remain the same.

If you have strong feelings about certain eating patterns (for example, maybe you’re an evangelical vegetarian or Paleo follower), try to put those feelings aside so you can zero in on your client’s values and needs—rather than an eating pattern they think they “should” follow.

What you might find is that most clients truly don’t care about extreme eating measures like giving up meat or giving up carbs. They just want to get healthier, leaner, and fitter—and they don’t care what eating pattern gets them there.

How do we know this?

Data.

Each month, roughly 70,000 people use our free nutrition calculator. They tell us what kind of an eating pattern they want to follow, and our calculator then provides them with an eating plan—with hand portions and macros—that matches their preferred eating style. We give options for just about everything, including plant-based eating and keto.

What eating pattern do most people pick?

The “eat anything” pattern. In fact, a full two-thirds of users choose this option, with the remaining third spread across the other five options.

In other words, they don’t particularly care what they eat as long as it helps them reach their goals. Interestingly, of the many options we list, people choose fully plant-based and keto diets the least.

So rather than fixating on a “best” diet, help clients align their eating choices with their goals and values.

Ask questions like: What are your goals? What is your life like right now? What skills do you already have (can you soak beans and eat hummus and veggie wraps)? What are the foods you like to eat that make you feel good?

Encourage clients to replace what they remove.

The more foods on someone’s “don’t eat” list, the harder they must work to replace what they’re not eating.

For fully plant-based eaters, that means replacing animal protein with plant proteins found in seitan, tofu, tempeh, beans, and pulses.

For Paleo, that means replacing grains and dairy with vegetables, fruits, and sweet potatoes.

For keto eaters, that means replacing all carbs with vegetables and healthy fats like extra virgin olive oil, nuts and avocado.

Don’t just offer advice on what to eat. Spend time on how.

At Precision Nutrition, we encourage people to savor meals, eat slowly, and pay attention to internal feelings of hunger and fullness. We’ve found that these core practices alone can drive major transformation—and may be even more important than the food people put on their plates.

(Learn more about the benefits of eating slowly.)

Help them focus on being better, not perfect.

Think of nutrition as a spectrum that ranges from zero nutrition (chips, sweets, and highly refined foods) to stellar nutrition (all whole foods).

Most of us fall somewhere between those two extremes—and that’s okay, even preferred. After all, we see huge gains in health when we go from zero nutrition to average or above average.

But eventually, we experience diminishing returns.

The difference between a mostly whole foods diet and a 100 percent whole foods diet? Marginal.

So rather than aiming for perfect, it’s more realistic to try to eat a little better than you are now.

For good health, a little better for most people involves eating more minimally-processed whole foods, especially more vegetables and more protein (whether from animal or plant foods).

If your clients eat carbs, they’ll want to shift toward higher-quality options like:

- fruit

- whole grains

- beans

- legumes

- starchy tubers (such as yams and potatoes)

If they consume added fats, they can challenge themselves to showcase healthier choices such as:

- avocados

- nuts

- seeds

- olives and olive oil

Depending on the person, that might involve adding spinach to a morning omelet, adding grilled chicken to their usual lunch salad, snacking on fruit, or ordering a sandwich with guac instead of mayo.

These might sound like small actions—and that’s precisely the point. Unlike huge dietary overhauls, it’s these small, accessible, and sustainable actions that truly lead to lasting change.

More than 100,000 clients have taught us:

Consistent small actions, repeated over time, add up to big results.

And here’s the beautiful part: When you zero in on these smaller, more accessible practices, you’ll stop locking horns with clients whose beliefs fall on the opposite side of the meat vs. meat-free debate as your own.

Instead, you can work together to build universal skills and actions that everyone needs—more sleep, eating slowly, more veggies—whether they eat meat or not.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, goals, and personal preferences—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

What’s it all about?

The Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification is the world’s most respected nutrition education program. It gives you the knowledge, systems, and tools you need to really understand how food influences a person’s health and fitness. Plus the ability to turn that knowledge into a thriving coaching practice.

Developed over 15 years, and proven with over 100,000 clients and patients, the Level 1 curriculum stands alone as the authority on the science of nutrition and the art of coaching.

Whether you’re already mid-career, or just starting out, the Level 1 Certification is your springboard to a deeper understanding of nutrition, the authority to coach it, and the ability to turn what you know into results.

[Of course, if you’re already a student or graduate of the Level 1 Certification, check out our Level 2 Certification Master Class. It’s an exclusive, year-long mentorship designed for elite professionals looking to master the art of coaching and be part of the top 1% of health and fitness coaches in the world.]

Interested? Add your name to the presale list. You’ll save up to 30% and secure your spot 24 hours before everyone else.

We’ll be opening up spots in our next Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification on Wednesday, April 8th, 2020.

If you want to find out more, we’ve set up the following presale list, which gives you two advantages.

- Pay less than everyone else. We like to reward people who are eager to boost their credentials and are ready to commit to getting the education they need. So we’re offering a discount of up to 30% off the general price when you sign up for the presale list.

- Sign up 24 hours before the general public and increase your chances of getting a spot. We only open the certification program twice per year. Due to high demand, spots in the program are limited and have historically sold out in a matter of hours. But when you sign up for the presale list, we’ll give you the opportunity to register a full 24 hours before anyone else.

If you’re ready for a deeper understanding of nutrition, the authority to coach it, and the ability to turn what you know into results… this is your chance to see what the world’s top professional nutrition coaching system can do for you.

The post The modern diet dilemma: Is it better to… eat meat? Go vegan? Something in between? The truth about what’s right for you. appeared first on Precision Nutrition.

Powered by WPeMatico

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.